Welcome to Unsend It, an occasional newsletter where I explore uncertainty, growth, identity, and change through the lens of my rock climbing.

I’ll release a new essay every now and then (no strict cadence at the moment — just writing when I want to).

If you’re not a climber, my goal is to make this relatable to your life. Climbing has a lot of jargon, so I’ll try my best to explain the weird terms we use. But know that my goal isn’t to make this newsletter about climbing training. My goal is to explore broader lessons around uncertainty, growth, and change through my experiences as a climber.

This first essay’s on embracing non-linear growth. Enjoy.

In 2018, I fell in love with climbing because it made me feel like I was in a video game.

Every climbing session I was leveling the fuck up. First session, I sent (completed) my first V11! Second session, V2. Third, V3s. Eventually, I can send V6s now. I’m Super Mario, leveling up the grades I’m able to send.

Climbing provided me a path of linear growth. The more I sessioned, the more I grew in a singular direction.

The first time I climbed was at a gym in my hometown, Temecula. December 2017. I was visiting my family while on PTO. My brother asked me if I wanted to try climbing. I said sure.

The second time I climbed was at Steep Rock East Harlem in January 2018 — a 15-minute walk from my Upper East Side apartment.

I grew a lot as a climber the next 4.5 years. I’m now sending V8s and 5.12a’s outside.

While this seems like linear growth, I actually think that my growth as a climber has been non-linear. More practice didn’t exactly mean more sends.

Expanding beyond bouldering: nonlinear growth

In 2020, I became an outdoor boulderer. Bouldering is when you climb without ropes — usually 5-15 feet off the ground, using a crash pad to protect your falls.

In June 2020, I left New York to move back in with my parents while working my remote job. My brother lived at home too. We liked to climb, but the gyms were closed. So we started bouldering outside.

In, March 2021, I send my first outdoor V4. Jones’n in Las Vegas. (My favorite V4 to this day.)

In April 2021, I send my first outdoor V5. Serengeti in Bishop, CA.

In December 2021, I send my first outdoor V6. Pink Lady in Saint George, Utah.

My bouldering grew linearly. More trips led to more difficult sends. More input, more output. 📈 📈 📈

Then, I tried toproping outside for the first time. February 2022. Toprope is different from bouldering: you climb with a rope attached to you, while the rope is secured on an anchor above you. In bouldering, you climb no higher than 15 feet off the ground. In toprope and sport climbing, you can climb as high as 90 feet.

My friend Adam went out of his way to teach me. I really enjoyed learning toprope. The thrill of being high off the ground, the calm state you put your mind in, knowing you’re secure and trust your partner with your life. Exhilarating.

A year-and-a-half later, I send my first outdoor 5.12a — a pretty challenging grade for someone who picked up rope climbing a year-and-a-half later. I did this on lead, rather than on toprope. As I lead the route, I clipped quickdraws into predrilled bolts throughout, and clipped my rope through my quickdraws. This means if I fall, I can fall between ~5-20 feet. If I fall on toprope, I’d fall ~1-2 feet. Lead climbing is more mentally challenging than toprope because you fall for longer distance if you don’t send the route. So I was very proud of leading my first 5.12a a year-and-a-half after doing my first toprope.

I wanted to do more than just progress my bouldering, I wanted to progress in different styles of climbing.

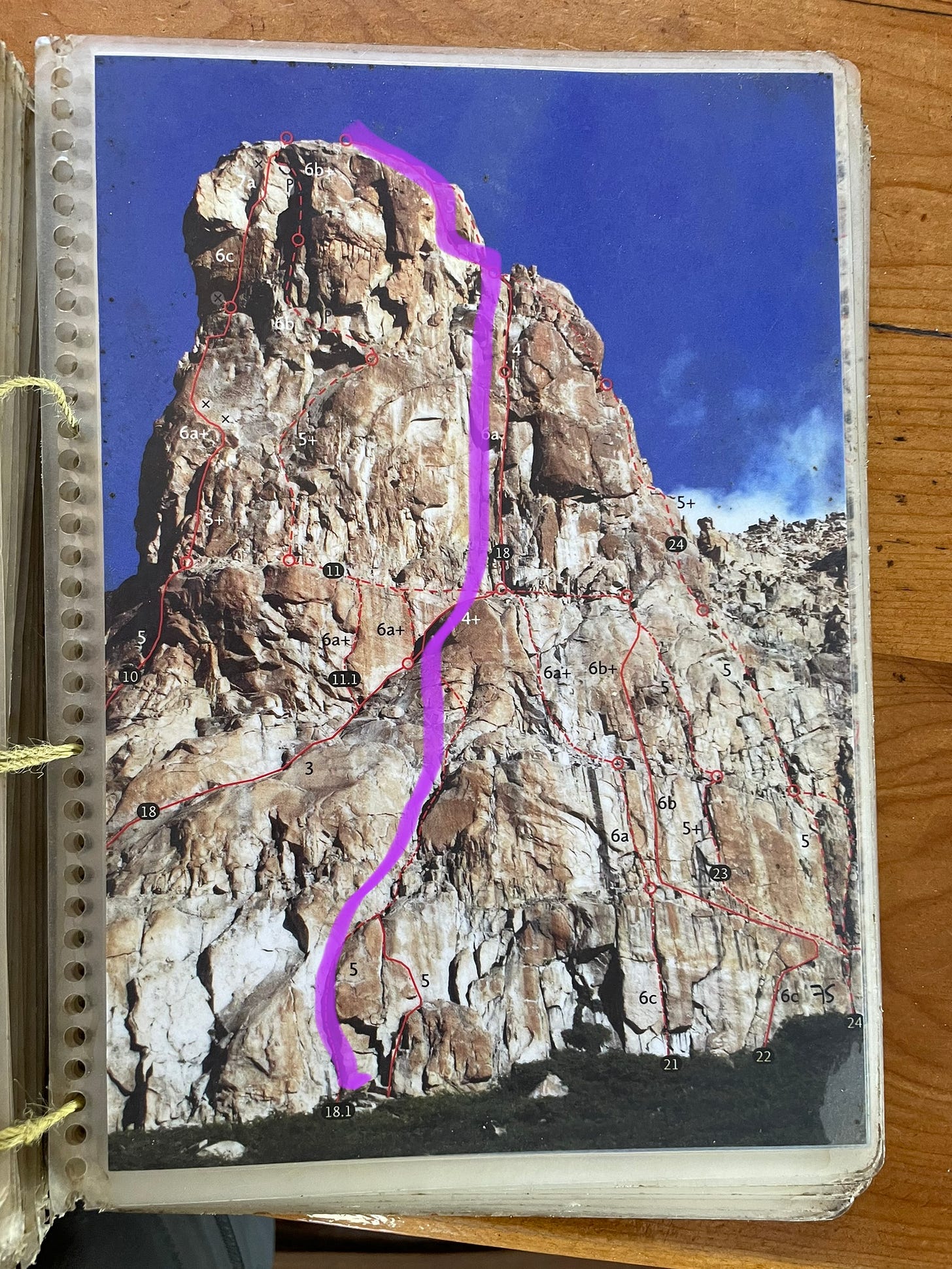

December 2022, I do my first multi-pitch follow in at the Frey (in the Patagonia region of Argentina). I did this with an experienced multipitch guide. Multi-pitch is very different from sport climbing in that you climb multiple routes instead of a single route. You get as high as 300-500 feet up. Maybe even higher. Very different skills: you need to know how to keep yourself safe throughout the entire time.

People tend to gravitate towards what they’re good at

Throughout my travels, I’ve met experienced boulderers who've never climbed on a rope. They’re afraid to fall.

I’ve also met experienced sport and multi-pitch climbers who are scared to boulder because they’re afraid to fall.

What’s interesting to me is that both camps are afraid of falling. But they’ve mastered falling in their specific style. Falling is a skill they’ve learned, so they have the capacity to learn how to fall in a different style. But the fear is still there.

We tend to get scared of things we haven’t tried. And we’re comfortable with what we know.

This is why many boulderers just boulder, many sport climbers just sport climb, and many multi-pitch climbers just multi-pitch climb.

Many traditional climbers I’ve met jokingly-but-sincerely shit on bouldering. And then they send their first boulder and love bouldering. Many boulderers I’ve met jokingly-but-sincerely shit on rope climbing. And then they do their first sport or trad route and love rope climbing.

Our growth mindset somehow finds its way into becoming a fixed mindset as we get comfortable with what we’re good at.

I don’t ever want to be the type of climber who’s afraid of other styles of climbing. Who only grows linearly. I want to grow nonlinearly.

I want to be able to send V9, be able to comfortably lead a multi-pitch, and maybe even team up with others to do my first bigwall in Yosemite someday.

Why limit yourself?

I think it’s good to have a specialty. Bouldering is my specialty. But when that specialty limits what you think you’re capable of, branch out. When that specialty is in the way of what you want, find out what’s blocking you and go for it.

I struggle to understand why more people aren’t fascinated by it all. At the end of the day, it’s all climbing. What separates a boulderer who only sticks with bouldering and a climber who’s excelled in different styles is their mindset. Are you willing to suck at a new thing?

I’m reminded of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind:

In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s mind there are few.

I think people also stick with growing in one direction because society has scripts that train us to think that growth is only linear.

You go to Kindergarten. Then first grade. Then second grade. Eventually fifth. Then high school. Then college. Then grad school or medical school or law school. Then job. Then a higher position with more responsibility and more salary. Eventually you’re like: is this what I actually want?

I don’t have beef with linear growth. I have beef when we think our only way of growing is linear.

Goals are great as long as you choose them

I’m still motivated by linear growth. I set a goal this year to send my first V8. I did just that in Squamish earlier this month.

Having these goals gave me direction. They helped me direct my effort. They tailor my gym sessions so that I’m consistently moving towards those goals. They force me to make decisions about how I spend my time at the crag (an outdoor climbing area). I know exactly what I need to do today to get closer to my yearlong goal.

Goals are a good thing! As long as you choose that to be your goal, rather than assume that it needs to be the goal.

Many new climbers immediately assume their next goal “should” be the next V-grade. Rather than actively choose to make it their goal to send the next grade. The linear growth trap. Not all growth is linear. Growth can also be:

“I’m practicing sending more problems within 2-5 attempts.”

“I’m trying to be more aware of when to rest on a sport route.”

“I’m going to make this month about having fun, rather than sending harder.”

“I’m going to try my first trad route today.”

“I’m going to take a break from climbing.”

You are the author of how you want to grow.

Mix different knowledge and skills

Do you often come across people for whom, all their lives, a "subject" remains a "subject," divided by watertight bulkheads from all other "subjects," so that they experience very great difficulty in making an immediate mental connection between let us say, algebra and detective fiction, sewage disposal and the price of salmon--or, more generally, between such spheres of knowledge as philosophy and economics, or chemistry and art?

—Dorothy Sayers in The Lost Tools of Learning

To extend this insight beyond climbing: think about how you could draw more connections between different subjects and skills in your life.

Being a boulderer has helped me lead my first 5.12a. Practicing sport climbing helped me send longer, endurance-y boulder routes. And being a sport climber and boulderer helped me do my first multi-pitch.

Before climbing, I was a competitive breakdancer, so body awareness and technique came natural to me in climbing. I also do yoga here and there, which helps increase my flexibility and helps me focus on my breath while I climb.

Each unique discipline feeds into other disciplines in my life. They’re intertwined trees that grow together.

Maybe you draw well, you’re an ok photographer, and have a background in mechanical engineering. You don’t have to be the best photographer to create something interesting. Maybe you can sketch out a dream bridge of yours, take photos, and post it on Instagram.

Maybe you’re a web designer who wants to blog more. You can design your own blogs where you write too.

Maybe you cook, love to teach, and are passionate about serving communities of color. You can start teaching cooking lessons for people of color who want to become better home cooks.

There are many possible connections between disciplines, subjects, skills. It’s up to you to see those connections. Don’t divide them into neatly divided subjects. Get messy with your interests. Feed them into each other. And witness the nonlinear growth.

V-grades indicate how difficult a bouldering problem is. V0 is considered very easy, V5 is considered moderately difficult, V16 is considered incredibly difficult. Grades are super subjective. If you don’t climb, just know that it’s hard, no matter the grade.

Linear growth is something that I found very difficult with learning a language. It seems to resist it. You cannot become linearly better at a language because language is so much about context. I can improve in my abilities to speak Spanish in a restaurant, but then when I take a yoga class, I suddenly go back 3 steps.

I have also noticed that growth often happens in periods of plateaus followed by spurts. The idea that we should always be improving linearly doesn't acknowledge the time it sometimes takes our body and mind to absorb and organise new information. It's helpful when you are not seeing a lot of progress to remind yourself that you are doing the ground work that will allow for what is likely a big improvement in future

I think all growth is non-linear whether we realize it or not. As you said with the school analogy: it is not normal to go back to kindergarten after high school but that's exactly what happens to you when you mix things up on you path to become better at something(s).

When I started kettlebelling in 2020 I approached everything as a linear path (and honestly, weightlifting kind of lend itself easily to that kind of thinking): more reps, more weight, more sets, more TUT (time-under-tension, basically the ratio between active time and rest time).

At the same time I decided to lose weight, and I lost a lot of it. I then realized that I was burning at both ends: strength endurance (which I never really trained up until then) requires energy and mass, I was sabotaging myself. I was doing the kettlebell equivalent of ego lifting.

I then started learning about programming and self-coaching: I started to improve when I bought an adjustable kettlebell that allowed me to alternate between a lighter and heavier weight, and progressively increase both. That literally puts you on a see-saw path of continuous improvement (seeing the sinusoidal graph with the median trend growing over time is very instructive).

This year I took another step in disrupting any linear path I was getting back into by taking a kettlebell instructor course: I had to go down in weight (from 26kg to 12) because there are some mandatory movements I have to do in the final test which I am crappy at, because in 3.5 years I've never done them...because they were difficult and I was better at other movements.

It just seems right that if I want to teach and train others the first one who needs to get uncomfortable and "walk the walk" it's me.